Is the World Heading for a Soft Landing in 2026?

A “soft landing”[1] once looked like the default outcome for 2026: inflation gliding back towards target, growth slowing without tipping into recession, and unemployment staying low. Through 2024 and early 2025, that’s broadly how markets were priced. As 2026 approaches the picture is less reassuring. Forecasts are converging on slower-than-trend global growth, while the range of possible outcomes is widening some still expect a gentle slowdown and orderly policy normalisation, others warn that high debt, stretched equity valuations and pockets of financial fragility could turn that smooth glide path into something far bumpier (Scope Ratings, 2025).

Major institutions now see not just weaker growth, but a different growth mix. The OECD expects the world economy to expand at rates below its pre-pandemic average, with inflation easing but remaining sticky in several advanced economies amid higher-for-longer borrowing costs, subdued investment and persistent geopolitical tensions (OECD Economic Outlook, 2025). The global cycle is increasingly uneven: the United States remains relatively resilient but is projected to slow from 2.8% growth in 2024 to 1.5% in 2026; Europe is held back by weak investment and policy uncertainty; China faces a structural downshift as demographics, tariffs and a long property correction weigh on activity; and many emerging markets offer pockets of strength that are too small to shift the global aggregate (Financial Times, 2025). Credit analysts such as Moody’s underline that risks around this baseline are skewed to the downside, even as AI and green technologies offer medium-term productivity upside (Moody’s Ratings, 2025).

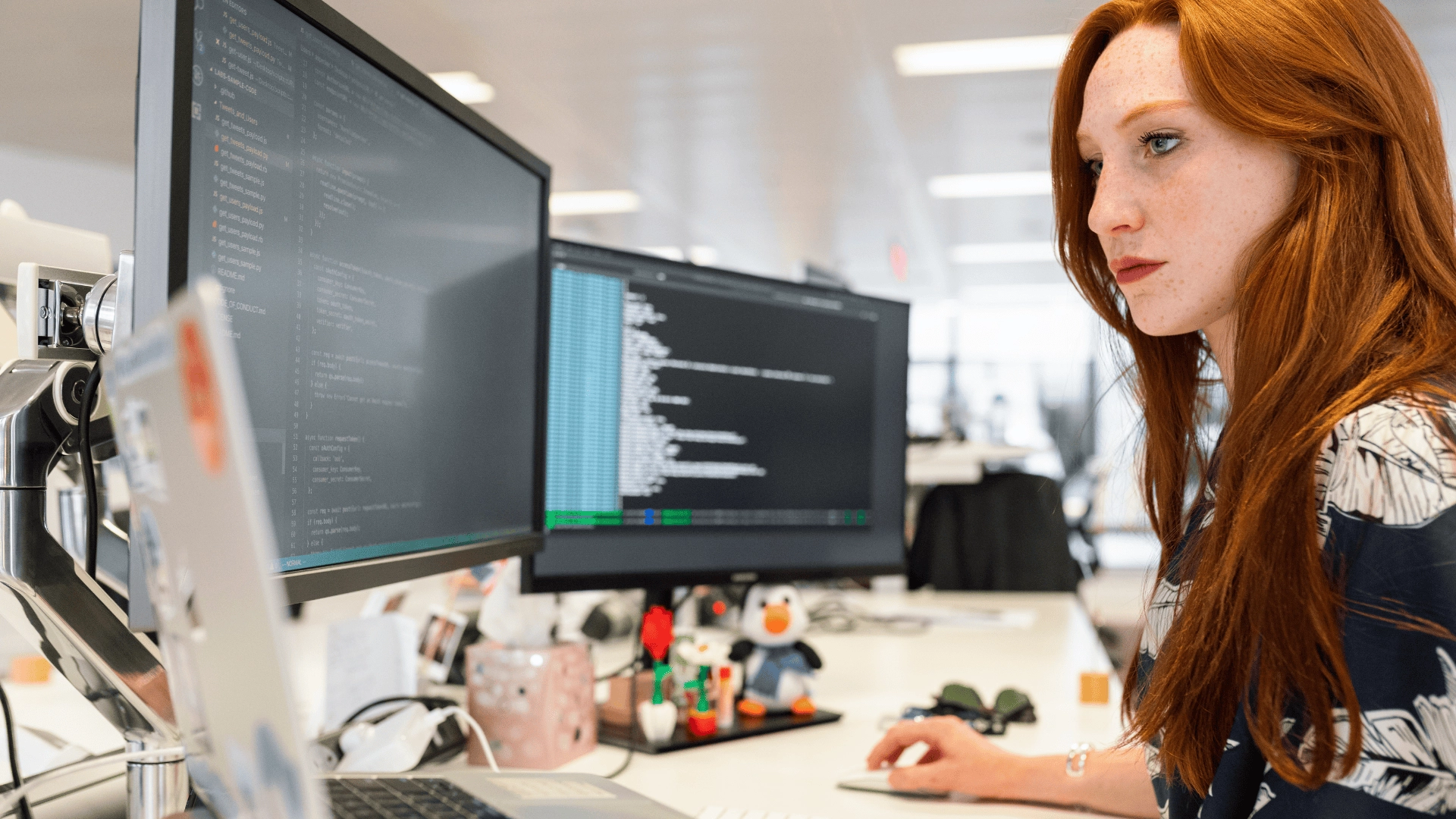

In such an uncertain environment, the tools we use to read the data matter as much as the headlines. This is where robust econometric software like Stata, and the expertise provided by Timberlake Consultants, become particularly valuable. From panel models and VARs to scenario analysis and forecasting routines, Stata allows researchers, policymakers and investors to stress-test different soft-landing and hard-landing paths, quantify risks and visualise alternative trajectories for growth, inflation and unemployment, while Timberlake’s training, technical support and consultancy help turn IMF, OECD and market datasets into concrete, decision-relevant insights.

Against this backdrop, the question for 2026 is not simply “soft landing or recession?”, but whether the world can navigate a slower, more fragmented expansion without triggering a financial accident. The rest of this blog explores what a soft landing really means today, the fault lines that could derail it, and what this implies for investors positioning portfolios for the year ahead.

(1) A "soft landing" refers to a situation where central banks successfully slow an overheated economy, bringing inflation down and cooling growth, without causing a recession or a sharp rise in unemployment.

The Inflation and Interest Rate Puzzle

On the surface, inflation looks like a problem largely solved. Headline rates in many advanced economies have fallen back towards central banks’ targets, energy and food prices have eased from their peaks, and the extreme supply chain bottlenecks of the post-pandemic period have mostly unwound (Lorié, 2024). Shipping costs are lower, delivery times are shorter, and the panic around missing components and empty shelves feels like a different era.

But beneath the calmer surface, the picture is more complicated. Core inflation, which strips out volatile items like food and energy, remains sticky in several countries, and the forces that could keep it elevated have not gone away. Slower globalization and more onshoring can make goods more expensive to produce; aging populations and tighter labour markets put upward pressure on wages; and the transition to cleaner energy requires huge upfront investment that can filter through to prices.

This is where the real puzzle for 2026 lies. If inflation doesn’t quite return to the pre-COVID world of ultra-low, predictable price growth, the “neutral” level of interest rates may be higher than households and businesses were used to in the 2010s. That would mean mortgage rates staying less forgiving, corporate borrowing costs remaining elevated, and governments facing a harsher arithmetic on already large debt piles.

Central banks are therefore walking a tightrope. Cut rates too quickly, and they risk reigniting inflation or fuelling new asset bubbles; keep policy too tight for too long, and they may choke off growth just as the full impact of earlier hikes is working its way through the economy (QuillMix, 2025). The way policymakers manage this trade-off, how fast they ease, how clearly, they communicate, and how they respond to new shocks, will be one of the decisive factors determining whether 2026 feels like a controlled cooling or the beginning of something much rougher.

Diverging Growth Paths: Asia, Europe and the US

One of the clearest themes in the 2025-2026 outlook is just how uneven global growth is likely to be across regions. Emerging Asia is still expected to do most of the heavy lifting, even if its pace is slower than in the pre-COVID boom years. Recent projections suggest that output in Asia and the Pacific will expand by roughly 4% a year in 2025-2026, about twice the rate forecast for many advanced economies (IMF, 2025; Lorié et al., 2024). Within this, China remains a key driver: its real GDP is forecast to grow by about 5% in 2026, supported by front-loaded policy measures, before easing to 4.5% in 2027 as fiscal stimulus wanes (Morgan Stanley, 2025). While this marks a clear step down from past highs, it still leaves emerging Asia as the main engine of global demand, helped by resilient domestic consumption and investment in technology and green infrastructure.

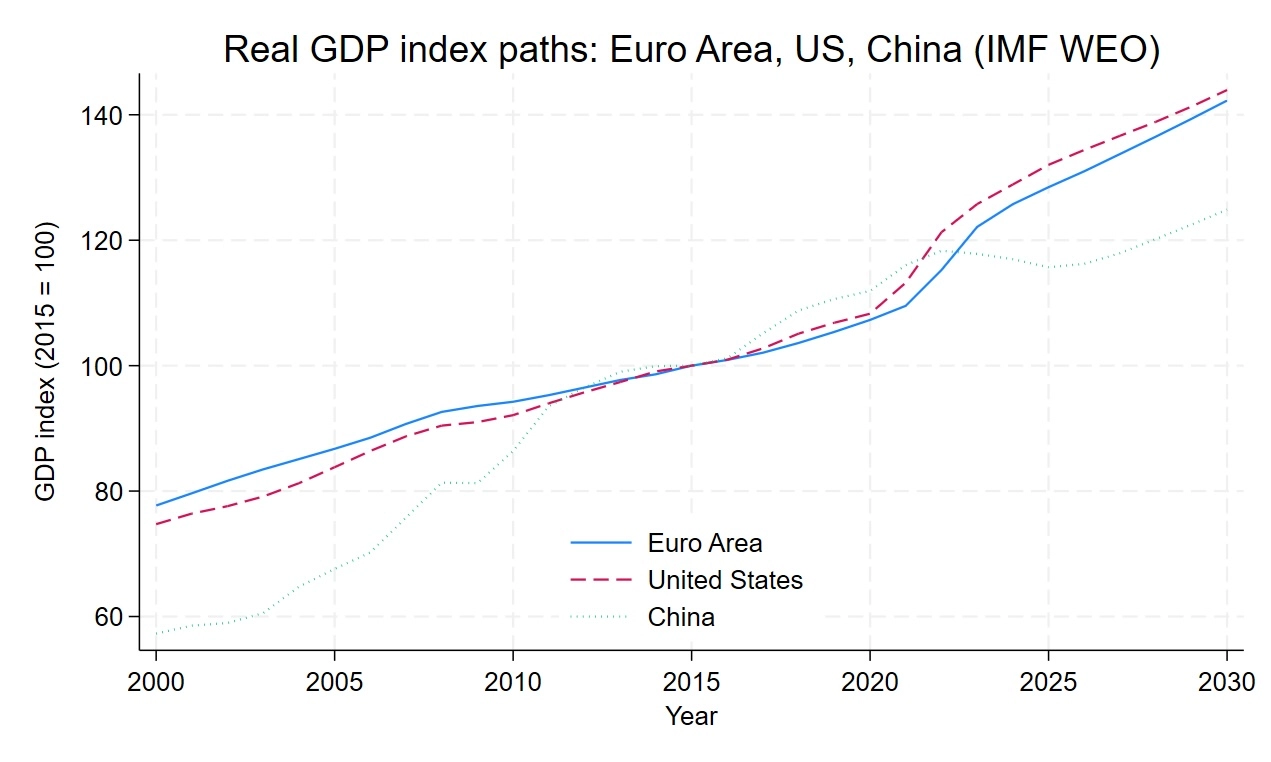

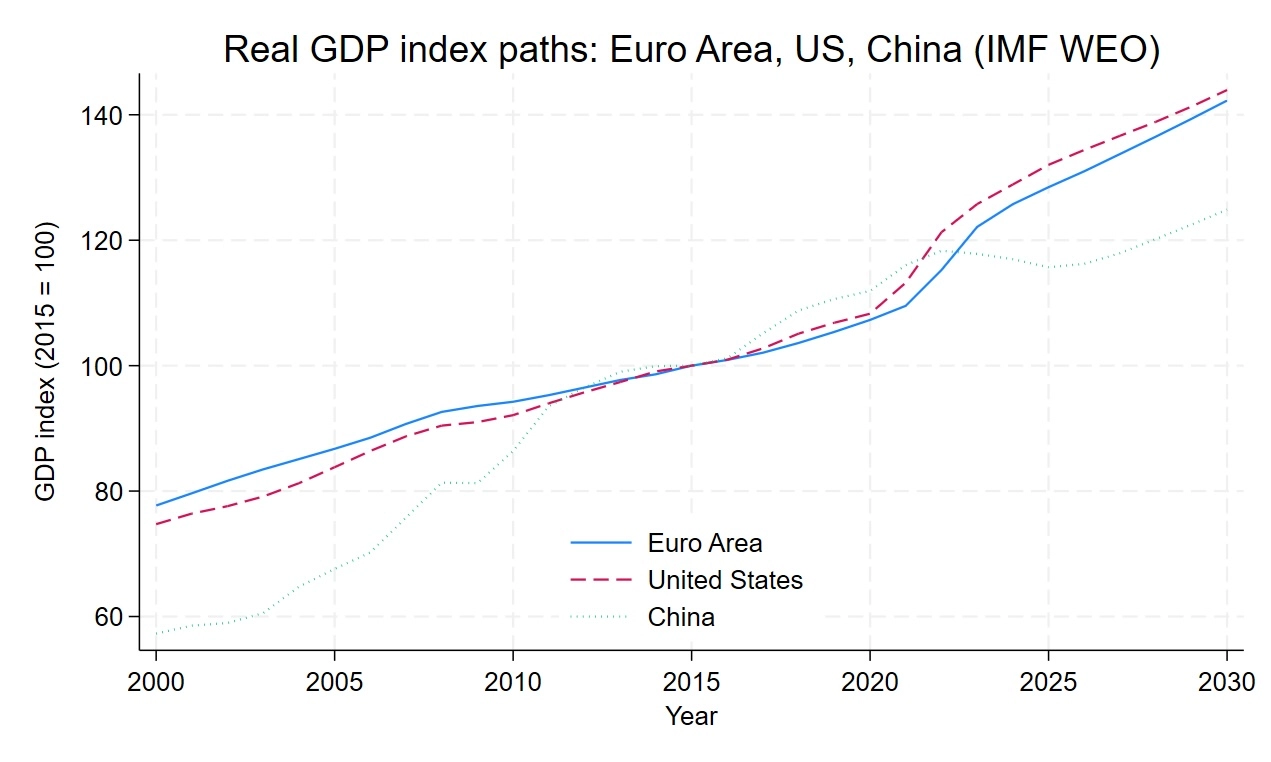

Figure 1 helps put this divergence into perspective. From 2000 to the mid-2010s, the euro area and the United States move largely in tandem, with the US grafually pulling ahead after 2017. China's trajectory is much steeper in the early 2000s, reflecting its rapid catch-up phase, but the curve flattens noticebly after 2015 as structural headwinds build. In the shaded "IMF projections" period (2024-2030), the US is expected to retain a modest lead over the euro area, while China continues to outpace both but a much more moderate speed than in the past. Taken together, the figure underscores a more balanced-but slower-global growth landscape, with no single region delivering the kind of outsized gains that characterised earlier decades.

Figure 1: Figure X. Real GDP index paths: Euro Area, United States and China, 2000-20230. Real GDP index, 2015=100 (IMF WEO October 2024 projections). Shaded area (2024-2030) denotes IMF projections. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, October 2024.

The picture in Europe is markedly weaker. The euro area is projected to grow, but only slowly, with forecasts hovering around 1-1.5% per year through 2026 (OECD, 2024). Several headwinds are at play: subdued consumer confidence, tight financing conditons and curcially, a manufacturing sector still adjusting to higher energy costs and sofer external demand, especially from China (Bank of Finland, 2024; Lorié, 2024). Germany, as an energy-intensive, export-orientated economy, remains under pressure, and its industrial slowdown continues to weigh on the wider euro area recovery.

By contrast, the United States enters 2026 from a postion of relative strength. Inflation has largely been brought under control, giving the Federal Reserve room to begin loosening policy, while household balance sheets and labour markets remain healthier than many had anticipated (Lorié et al., 2024; OECD, 2024). Consumer spending is still the main pillar of US growth, and most baseline forecasts see activity in 2025-26 outpacing that of other major advanced economies, even if the pace gradually cools (Deloitte, 2025; McKinsey & Company, 2025). The new US administration therefore inherits an economy that is, for now, fundamentally robust, meaning that any negative impact from trade or fiscal policy changes is more likely to emerge with a lag as we move deeper into 2026.

Taken together, this regional divergence complicates the global "soft landing" story. A world in which emerging Asia grows solidly, the US slows but avoids recession, and Europe struggles to gain traction is very different from the synchronised upturn investors grew used to in the 2000s. For policymakers and markets alike, the challenge will be managing these different speeds without triggering financial stress in the weaker links of the global economy.

The AI Factor: Productivity Engine or Disruptive Shock?

If there is one structural force almost guaranteed to shape the macro picture in 2026 and beyond, it is artificial intelligence. The first wave of generative AI tools, from ChatGPT-style assistants to code-writing models, grabbed headlines, but the real shift is AI moving from “demo” to “default” in how firms operate. By the mid-2020s, many companies are expected to embed AI into core workflows, from automating back-office tasks to optimising supply chains and tailoring products in real time (McKinsey & Company, 2025).

International organisations increasingly treat AI as a potential growth engine rather than a futuristic add-on. OECD “faster AI adoption” scenarios suggest that, if AI spreads through economies at a pace like past technologies like mobile phones, supported by reforms and better digital skills, it could add 0.3–0.4 percentage points to average annual GDP growth in G20 economies by 2050 (OECD, 2024). Compounded over time, that implies a meaningful boost to living standards.

However, this upside is neither automatic nor evenly shared. The benefits depend on whether firms can access the skills, data infrastructure and capital needed to deploy AI, and whether policy frameworks promote broad adoption rather than entrenching a few dominant players. At the same time, automation of routine tasks risks displacing workers even as demand grows for high-skill roles in AI development and governance. Without reskilling, safety nets and “responsible AI” regulation to tackle issues like bias and privacy, AI could deepen inequalities and fuel backlash rather than delivering broad-based prosperity (OECD, 2024; McKinsey & Company, 2025).

In practical terms, the AI factor for 2026 can be summarised in four dimensions:

· Labour-market disruption: Routine jobs are most exposed, while demand rises for advanced digital and analytical skills.

· Productivity potential: AI can raise efficiency, but the scale and timing depend on organisational change and complementary investment.

· Investment wave: Public and private spending on AI, cloud, data centres and infrastructure is creating a powerful capex cycle, and new bottlenecks.

· Regulation and trust: The balance regulators strike between innovation and control will shape where AI value is created and who captures it.

Whether AI ultimately supports a soft landing or complicates it will depend less on the technology itself and more on how quickly institutions, firms and workers adapt to this new general-purpose tool.

Conclusion

In the end, the question “Is the world heading for a soft landing in 2026?” doesn’t have a neat yes-or-no answer. What the data and forecasts suggest instead is a slower, more fragmented expansion: emerging Asia still doing much of the heavy lifting, the US decelerating but avoiding recession, and Europe struggling to regain momentum. Inflation is broadly under control but not fully tamed, interest rates are likely to stay higher than in the 2010s, and the risks around this baseline, from geopolitics to financial market corrections, are skewed to the downside. At the same time, powerful structural forces like AI and the green transition offer genuine upside for productivity and growth, but only if economies manage the transition without leaving too many workers, sectors or countries behind.

For investors, policymakers and analysts, this means treating 2026 less as a binary “soft landing vs hard landing” moment and more as the start of a longer adjustment to a new macro regime: lower trend growth, higher real rates, greater regional divergence and faster technological change. In that environment, careful scenario analysis, robust econometric tools such as Stata, and expert support from partners like Timberlake Consultants become essential for cutting through the noise, stress-testing assumptions, quantifying risks and identifying where the real opportunities still lie.

Francisca Carvalho, Lancaster University

Francisca is a third-year PhD student in Economics at Lancaster University. Her research focuses on climate risk factors and their impact on portfolio returns. She also teaches mathematics, econometrics, macroeconomics and microeconomics, to undergraduate and postgraduate students.

-

Bank of Finland. (2024, October 1). Inflation down but euro area’s manufacturing still struggling with high energy costs. Bofbulletin.fi.

-

Financial Times. (2025, August 5). Weak business investment threatens global growth, warns OECD. Financial Times.

-

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Regional economic outlook: Asia and Pacific. Navigating trade headwinds and rebalancing growth (October 2025). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org

-

Lorié, J. (2024, December). Economic outlook: On target for a soft landing? Atradius.

-

McKinsey & Company. (2025, September 29). Economic conditions outlook, September 2025. McKinsey & Company.

-

Moody’s Ratings. (2025, November 12). Global macro-outlook 2026 executive summary. Moody’s Investors Service. https://www.moodys.com

-

Moody’s Ratings. (2025, November 19). Corporates outlooks 2026 executive summary (by region): Outlooks 2026: Corporates are stable across major regions worldwide. Moody’s Ratings

-

Morgan Stanley. (2025, November 19). 2026 economic outlook: Moderate growth with a range of possibilities. Morgan Stanley.

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024). OECD economic outlook (Vol. 2024/2). OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). OECD economic outlook, interim report September 2025: Finding the right balance in uncertain times. OECD Publishing.

-

QuillMix. (2025, April 21). Economic forecast: What experts predict for 2026. QuillMix.

-

Scope Ratings. (2025, June 20). Global economic outlook: Mid-year 2025 – Trade, geopolitical and sovereign-debt risks, alongside sustained high rates, weigh on the macro-economic outlook. Scope Ratings.

-

Wolf, M. (2025, September 30). United States economic forecast. Deloitte Insights.